This discussion paper considers emerging approaches to defining, initiating, and governing Maritime Green Corridors, and puts forward recommendations in each area. These recommendations attempt to reinforce the most effective and impactful approaches while acknowledging the need for flexibility.

Executive summary

Maritime Green Corridors have swiftly become recognized as one of the most important tools to aid industry and governments in the decarbonization of the maritime sector. Building on the initial conceptualization put forward in The Next Wave (Getting to Zero Coalition, 2021) and the signatories of the Clydebank Declaration (as initiated by the UK Government, 2021), and responding to multiple requests from industry and governments taking an interest in the concept, the paper considers emerging approaches to defining, initiating, and governing Maritime Green Corridors, and puts forward recommendations in each area. These recommendations attempt to reinforce the most effective and impactful approaches while acknowledging the need for flexibility.

By definitions, this paper means the first principles and terms of engagement being used to underpin action on Green Corridors. It takes the simple approach of examining how different actors are defining “Green” – in terms of types of impact and level of ambition – as well as how they define a “Corridor” in terms of operational scope and emphasis.

By initiating actions, this paper means the approaches taken to prioritizing different corridors, engaging stakeholders, assessing feasibility and requirements, and “route mapping” the corridor’s overall development. Because the eventual governance of Corridors can take multiple forms (see below), these initial actions can be emergent and (ideally) complementary efforts undertaken in parallel or in coordination with each other.

By implementation, this paper means the approaches taken to governing and managing the many actions needed to deliver a Maritime Green Corridor. While implementation of policies and deployment of technologies has yet to begin, some of the alternative approaches to governance and management can already be identified.

This discussion paper is not built on formal research, but reflects the ongoing conversations held by the Global Maritime Forum with its partners, interested governments and leading actors in emerging Corridors. Members of the Getting to Zero Coalition’s Global Green Corridors Advisory Group provided feedback and input to draft versions.

What kind of activity is emerging?

A number of initiatives, partnerships, and studies have been announced during the first half of 2022, and more are expected. The illustration below includes information about 8 such announcements that had been made as of 1 June 2022. These include initiatives taken by industry and third sector actors, by governments, and in collaboration between the two. This illustration is not meant to be comprehensive but only to give an indication of activity at a point in time.

Figure 1: Emerging activity on maritime green corridors

What issues are being addressed?

The figure below summarizes some of the issues that these Corridor initiatives are grappling with in their early stages of development. These issues are explored in more detail in the body of the discussion paper.

Figure 2: Summary of issues faced by green corridor initiatives

Definitions

The Global Maritime Forum and Getting to Zero Coalition have emphasized the definition of a Maritime Green Corridor as:

Specific shipping routes where the technological, economic and regulatory feasibility of the operation of zero-emission ships is catalyzed by a combination of public and private actions.

This definition has influenced and continues to share much in common with other definitions in use (see Figure 1). However since other definitions have emerged, a review of the nuances and emphases can help provide clarity. These nuances essentially involve differing approaches to defining “Green” and to scoping what is meant by “Corridor”.

Figure 3: Definitions of green shipping corridors

Definitions of “Green”

One difference is whether stakeholders prefer to define “Green” in terms of emissions reductions per se, or whether the focus is on the technology and infrastructure to be deployed.

Emission-centric: The former approach, advanced in some part by the United States Green Corridor Fact Sheet as well as in the preliminary communications from the collaboration between the Port of Los Angeles and the Port of Shanghai, emphasises the potential to reduce emissions on given routes (though the US Framework also mentions technologies). Such approaches may also connect the reduction of emissions from deep-sea vessels to other, potentially shorter-term, sources of emissions (e.g. port operations, full chain logistics, etc.)

Technology-centric: The latter approach, emphasizing the demonstration and deployment of zero-emission technologies (fuels, infrastructure and vessels), has been more common. The US Framework mentions both “low and zero-emission” technologies without defining a subset of fuels. Lloyd’s Register refers to “Zero Carbon” rather than “Zero Emission,” though the associated analysis considers fuels with net-zero carbon feedstocks (e.g. blue and green methanol) in scope. The work of the Getting to Zero Coalition has emphasized the technologies associated with “Scalable Zero Emission Fuels” namely those that have the potential to achieve near-zero GHG emissions on a lifecycle basis while also scaling production in line with the pace of the transition. As opposed to the emission-centric approach, this approach addresses the need for targeted and coordinated technology demonstration and deployment to enable the long-term, large-scale decarbonization of the sector.

Corridor efforts looking to take a phased approach may wish to consider the Light Green/Dark Green typology developed by University College London. This allows for the inclusion of multiple fuels in a Corridor effort while maintaining clarity about what is needed to drive the overall transition.

Figure 4: Possible typology for green shipping corridors

Ambition

Different levels of ambition are possible within both approaches.

An emissions-centric approach could, for example, adopt modest initial reduction targets to allow for immediate action, and increase stringency over time. No corridor has to this point established such an emissions-centric ambition trajectory.

A technology-centric approach could manage ambition through milestones or indicators for project initiation, partners engaged, technology development or deployment, for example the number of zero-emissions vessels in operation, the amount of scalable, zero-emission fuel available or other indicators related to the cost and performance of these technologies.

Recommendation

Maritime Green Corridors are likely to play a particular role in the transition to zero-emission shipping: as enablers of the ‘emergence’ phase, when new solutions are tested and demonstrated at scale to prepare for the coming period of rapid global diffusion. As such the role of Maritime Green Corridors is not to primarily to generate emissions reductions, but to help the industry reach the “tipping point” (estimated in a 2021 paper by the High Level Climate Champions, UMAS, and Getting to Zero to be around 5% of global shipping fuels) where zero-emission solutions begin to diffuse rapidly.

Figure 5: Green corridors in a transition context

A focus on incremental emissions reductions, even at a high ambition level, is likely to incentivize short-term measures such as technical efficiency improvements, the use of drop-in biofuels, and changes in port operations. While both might be desirable outcomes, neither requires the kind of end-to-end, full-value-chain coordination that a Green Corridor can provide. If scarce resources are diverted from the area where the need is greatest, that is, towards the establishment of new value chains for scalable zero-emission fuels, then Green Corridors will not have the impact needed.

While the need to achieve measurable emissions reductions is clear, we recommend that Green Corridor definitions include a clear reference to scalable, zero-emission fuels and associated technologies.

In terms of ambition, we recommend that Green Corridor efforts adopt target dates for numbers of vessels in commercial operations using a scalable zero-emission fuel (multiple targets will be appropriate if multiple fuels are included in the proposed fuel pathway), ideally with multiple milestones through 2030.

Definitions of “Corridor”

Clarity about what a “Corridor” should strive to encompass is also desirable. Different concepts include the following:

Port-centric

The corridors initiated by collaborating ports have understandably put the ports at the centre of the system, with decisions about which activities will be greened, with decisions about system boundaries, relevant cargo and voyages and even prioritized technologies likely to follow from the Ports’ priorities. In the Shanghai-Los Angeles corridor, for example, sets the system boundary at the port gate, so that port operations, cargo-handling, etc. are in scope. The importance of air quality issues and local community and environmental interests in both port cities are likely to have an influence on priority-setting and fuel choices.

Route-centric

Other corridors are less likely to be driven by ports. The mooted iron ore Green Corridor between Australia and East Asia builds on the strategic interests of companies in the iron/steel value chain, as well as on the energy strategies of Australia and Japan. With the route likely serviceable through bunkering in Australia alone, the focus will be on making the economics of fuel supply and chartering arrangements work, solutions that could be relevant to a number of voyages making a range of port calls in the region.

Pilot/demonstration project-centric

One approach to a Green Corridor is to emphasise direct investment in end-to-end pilots/scalable demonstration projects that prove feasibility of zero-emission shipping by demonstrating the entire chain in operation. These pilots can generate learning and build confidence in technologies but are not necessarily replicable if they are designed as one-off undertakings.

Programmatic/Niche market

A contrasting approach is to focus the corridor on developing the conditions for multiple actions, pilots, and demonstrations, and eventually, to enable full-scale commercial operations. In such an approach the focus is on creating and maintaining the enabling environment rather than on any given demonstration per se. The port-led initiatives (LA-SH, Mon-Antwerp, Seattle-Vancouver-Juneau) appear to be taking such a programmatic approach, but it remains to be seen whether the governments of the Clydebank signatories will choose to provide direct support to pilots and demonstrations or to focus efforts on the enabling programme (policies, guidance, open innovation funding etc.).

Recommendations

Different approaches are a natural outcome of different initiative-takers and government structures. However, generally speaking, we recommend

A programmatic emphasis on the enabling ecosystem as an essential part of promoting scalability and learning

A strategic emphasis on overcoming obstacles to commercialization faced by shipowners, charterers and cargo-owners (the “software” of Corridors), as opposed to a narrower emphasis on infrastructure and technology (the “hardware” of Corridors)

Initial actions

Establishing Green Corridors requires some initial actions – many of which will be needed even before the “Corridors” have an institutional form.

Evaluation, assessment, and prioritization

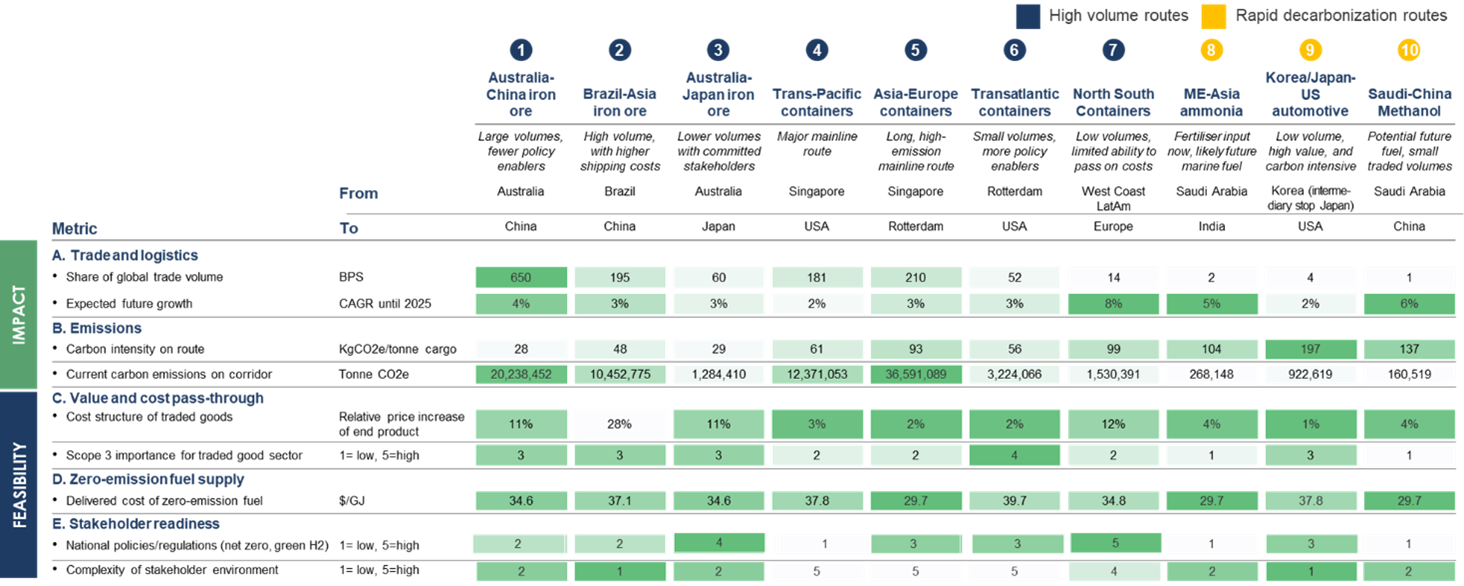

A number of types of evaluation/assessment may be useful in identifying opportunities and prioritizing some routes over others.

Port readiness assessments – Both the IAPH and the US government (within the Zero-Emission Shipping Mission) have advanced the notion of ‘port readiness’ assessments as an input to determining which Green Corridors might be feasible. These may assess operational readiness (IAPH) related to issues such as safe handling of new fuels, or they may attempt to determine the potential to develop suitable bunkering infrastructure based on potential for energy supplies, available land or infrastructure that can be repurposed (US/ZESM suggestion).

Whole system (modelled clusters) – UMAS on behalf of the Getting to Zero Coalition has developed an approach to modelling fuel demand clusters that can support prioritization of Corridors, essentially identifying which sets of existing voyages could be efficiently served by bunkering of new fuels. This analysis also incorporates a high-level assessment of potential fuel supply based on renewable energy resources.

Figure 6: Visualization of global “First Mover Routes” based on demand clustering

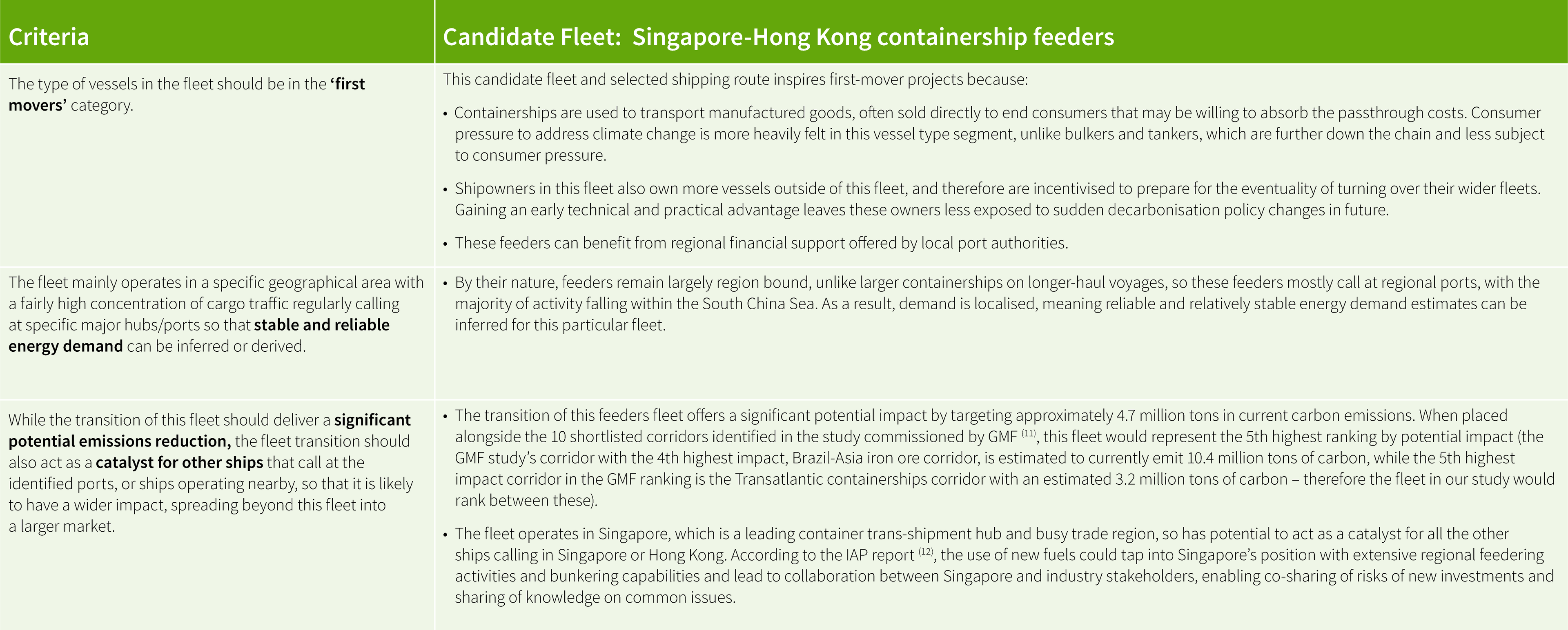

Whole system (multi-criteria) – The Getting to Zero report The Next Wave put forward an approach to evaluating corridors that assesses feasibility and impact through quantitative (emissions reduced, volume of trade, impact on cost of traded goods) and qualitative criteria (stakeholder readiness, policy environment).